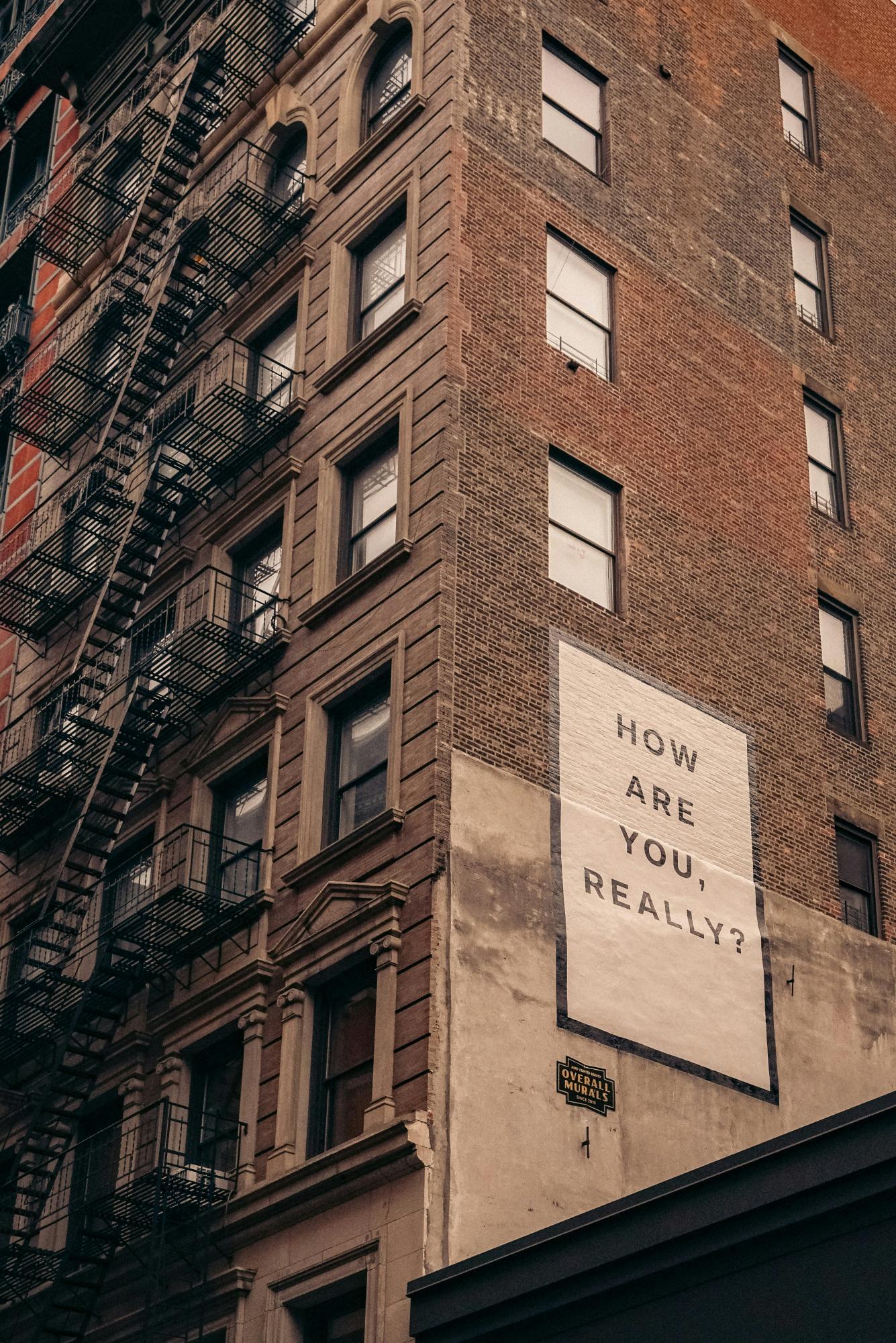

Not long ago, admitting to feeling overwhelmed or anxious was often met with silence or skepticism. Fast forward to the COVID-19 era, and conversations about burnout and mental health are everywhere, from kitchen tables to boardrooms. What happened to spark this dramatic shift?

The answer lies in a global crisis that exposed not only our physical vulnerabilities but also the deep emotional and psychological toll on modern life. As the pandemic disordered routines, blurred work life boundaries, and isolated communities, millions found themselves grappling with anxiety, depression, and burnout, often for the first time. What was once whispered about behind closed doors suddenly became a public conversation, fueled by shared experiences and an urgent need for change.

This awakening didn’t stop at mental health. The pandemic also disrupted education systems worldwide, leading to a decline in literacy rates, especially among children from underserved communities. At the same time, the stigma surrounding mental illness, long rooted in historical misconceptions and fear, began to fade. Society was forced to confront uncomfortable truths, and in doing so, began to foster greater empathy and understanding.

Understanding Burnout Among High-School Students

For High School students, this shift hit especially hard. The abrupt move to online learning and social distancing pulled students from classrooms, cafeterias and clubs, the very spaces where learning and identity building often took place.

“I was constantly anxious. There was no escape, no school dances, no sports, no talking to friends in the hallways,” Jasmin Cortes, a High School junior at OCHS said. “It felt like I was falling behind in everything, school, friendships, even life.

What many students like Jasmin were experiencing was burnout, not just feeling tired or unmotivated, but an intense, chronic exhaustion. Though often associated with adults, burnout among teens has skyrocketed in recent years.

“Burnout is a form of exhaustion caused by constantly feeling swamped,” a WebMD Editorial contributor said. “It happens when we experience too much emotional, physical, and mental fatigue for too long.”

The Stigma Surrounding Mental Health

Beyond academic loss, the emotional toll was enormous. For many teens, the pandemic spotlighted another hidden struggle, the stigma of mental illness. Long before COVID, mental health was often ignored or minimized in schools and households.

“Every day I’d just stay in my bed. I’d wake up…be on school in my bed and just get up to go eat…I just lost all motivation,” Daniela Rivera, a high school student from Cottonwood, Arizona said, in an interview with NPR. Isolated with only pre-recorded lessons and no live teachers or peer connection, Daniela’s mental health began to spiral. “I didn’t get a lot of things. I gave up completely.”

While students like Daniela once kept their emotions buried, the collective experience of isolation and stress helped normalize open conversations about anxiety, depression, and emotional fatigue. Research backs this up; according to the CDC, nearly 2 in 5 teens reported experiencing poor mental health during the pandemic, and 1 in 5 seriously consider suicide. These staggering numbers helped reduce the shame often associated with mental illnesses

“The pandemic got me into the mindset where, like, I’m just trapped in this house and I can’t do nothing,” Daniela said. “I have stuff I could do outside but, I just felt like I couldn’t even open the front door.”

Literacy Decline Amid the Pandemic

As students were fighting silent battles, their learning was also slipping through the cracks. For many, especially those in underserved communities, this meant falling behind in key skills like reading and writing, a crisis still being felt today. As schools work to recover from the academic fallout of the pandemic, educators are grappling with the complex roots of declining literacy. It’s not just one cause, but a combination of stressors, inequities, and disruptions that have set students back.

“We are still seeing the effects of COVID and long-term stress and trauma on students and their families,” Tiffany K. Smith, a professor of Western Education said. “This prolonged stress and trauma has research based-effects on literacy rates,” Smith said.

A study of 30 states by Harvard and Stanford universities on learning rebounds from the pandemic, released in early 2024, showed Oregon students were the only group that has failed to return to pre-pandemic levels in either reading or math skills.

Even as Oregon increased education spending, student performance hasn’t recovered. A 2024 Harvard and Stanford study found Oregon was the only state where students didn’t rebound in reading or math post-pandemic.

“There isn’t a single reason for declining literacy rates but rather many factors contributing to it.” Smith said.

Among those many factors, a growing concern is the rise in student reliance on artificial intelligence tools like; SnapchatAI, OpenAI, ChatGPT, etc… While these tools can support learning when used responsibly, they’re often being misused as shortcuts. Faced with mounting pressure from teachers to catch up and from parents to succeed, some students are turning to AI not to learn, but to cope.

”Technology can be a useful tool but it can also be a barrier,” Melissa Berg, Director of Student Services at Oregon City High School said. “There is academic pressure… students think AI will help them,” Berg said. “Remember that it’s a tool. Not something to write your papers on.”

But that reliance on AI, especially tools that generate text for students, may be doing more harm than good. With students using AI to complete writing assignments or even critical literacy skills like comprehension, analysis, and independent writing are being bypassed. Educators warn that this growing dependence may be a silent contributor to the nationwide decline in literacy rates, as students miss key opportunities to practice and develop foundational reading and writing abilities.

Schools’ response and path forward

As mental health came to the front, schools began responding. Some added mental health days to the calendar, hired new counselors, or brought mindfulness practices into home rooms.

“I think as a district we are really trying to make sure students feel important and heard,” Berg said. This reflects a broader effort by schools to prioritize student well being in the aftermath of pandemic related learning loss and emotional strain.

Still, the road to recovery is long. Addressing literacy decline, closing academic gaps, and supporting mental health will require sustained effort, community involvement and innovative approaches. But if the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that students are resilient, and with the right support, they can bounce back stronger than before.

“Know what you know, not what ai knows,” Berg said.